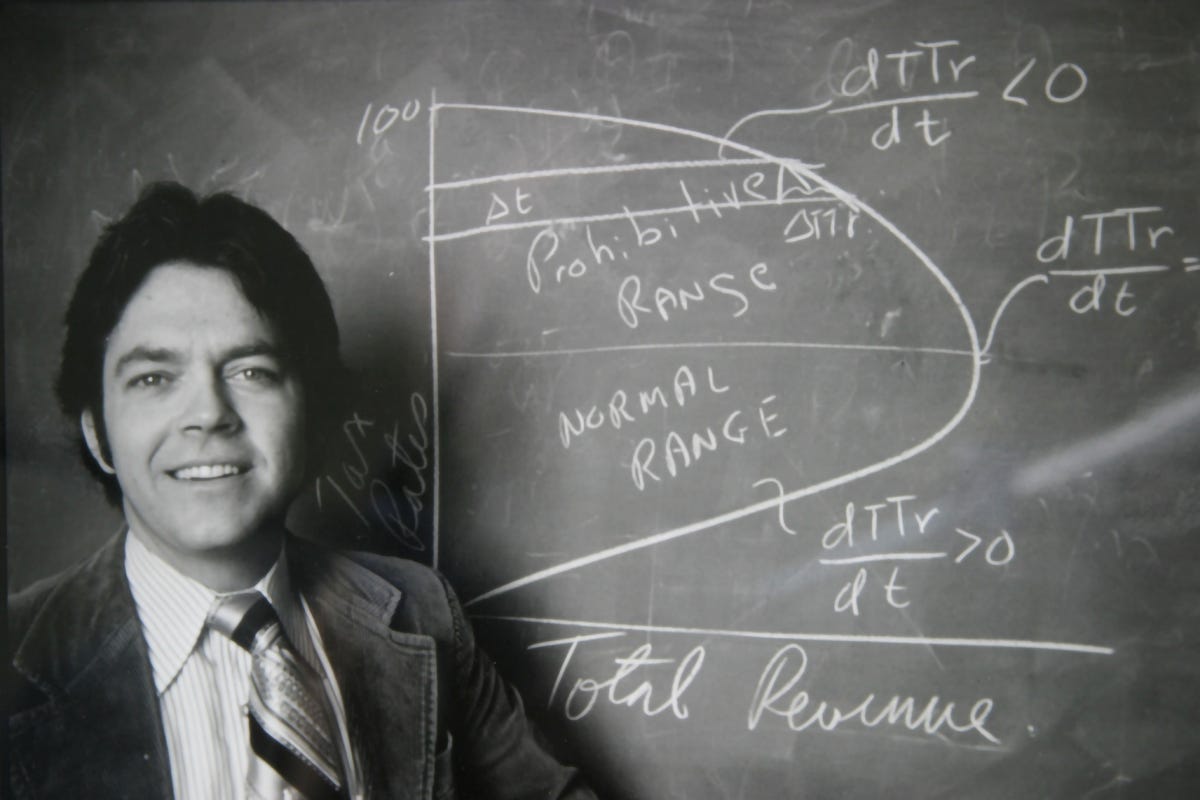

The Laffer Curve is a simple idea with large consequences. It says that tax revenue depends on tax rates in a non-linear way, zero tax raises nothing, one hundred percent tax also raises little once people stop working, investing, or shift income out of reach. Somewhere between those extremes there is a rate that maximises revenue. This is not only a point on a graph, it is a reminder that incentives matter, and that tax policy shapes behaviour.

Where the idea came from

The concept is most associated with Arthur Laffer, an American economist who popularised it in the mid-1970s. The story that he sketched the curve on a napkin for policy makers has become folklore. The underlying insight is older, it echoes centuries of public finance thinking from Ibn Khaldun to Keynes, yet Laffer gave it a clear, usable form for modern policy debate.

Why the curve is useful

We should use the Laffer Curve as a framework for three reasons.

It highlights incentives. When marginal tax rates rise, people work less at the margin, defer projects, shift income into deductions, or migrate. When rates fall with a broader base, compliance can improve and taxable activity can grow.

It forces dynamic thinking. Static models assume behaviour does not change. The curve reminds us that taxpayers respond, slowly at first, then all at once when thresholds are crossed.

It disciplines trade-offs. Governments need revenue for services and defence. The curve does not say low tax is always best, it says there is a point where higher rates collect less, and often hurt growth on the way.

The exact shape of the curve, and the revenue-maximising rate, varies by tax type, by time, and by how easy it is to move people and capital. In a world with mobile talent and digital capital, the curve is steeper and the peak arrives sooner.

Why growth is struggling in many Western economies

Western economies face weak productivity, ageing populations, and heavy public debt. On top of that, many rely on high marginal taxes on income, payroll, and capital, often layered with complex means testing and phase-outs that push effective marginal rates higher than headline rates suggest. This pushes behaviour toward avoidance, away from risk, and in some cases across borders.

People and firms vote with their feet. High earners relocate to jurisdictions with clearer rules and lower effective rates. Companies shift intellectual property and investment to friendlier tax bases. The result can be a smaller tax base at home, slower business formation, and a sense that growth is stuck in low gear.

How the curve helps explain country-level predicaments

United States. The federal code combines progressive income taxes, payroll taxes, and many phase-outs that create high effective marginal rates for certain bands. Add state and city taxes in high-tax states and you see migration toward lower-tax states. Capital gains realisations whipsaw with rate changes, a classic Laffer response. Broad-base, lower-rate reforms have tended to lift compliance and investment, while very high marginal rates have pushed income into shelters or timing games.

United Kingdom. A complex mix of thresholds and tapers creates sharp cliffs, for example the effective marginal rate spike when the personal allowance is withdrawn. High taxes on labour and an unstable corporate regime have coincided with weak business investment. When the effective marginal wedge rises, more high earners consider non-dom regimes abroad or move within Europe and the Gulf.

France. Historically high labour taxes and wealth taxes drove visible tax migration among high earners and entrepreneurs. Reforms that narrowed the wealth tax to real estate and reduced some labour costs helped, yet the long period at the upper end of the curve left scars in business formation and private investment.

Nordic countries. These are often cited as counter-examples. They run high tax ratios, but with broad bases, simple rules, strong property rights, and heavy reliance on consumption taxes that are harder to avoid. Their lesson is not that very high rates always work, it is that design and credibility matter. Even there, pressure shows up in capital-intensive sectors and in the tug of war to keep talent from moving.

Ireland and the Netherlands. Lower, stable corporate tax regimes and predictable rules attracted mobile capital and high value jobs. This is the Laffer Curve in the corporate domain, a lower rate on a broader base that collects more from a larger activity set.

These cases point to the same mechanism. When marginal wedges get too large, activity shifts, sometimes slowly, sometimes abruptly. The tax base shrinks in the places that push past the peak.

What happens when you push past the peak

When policy sets rates above the revenue-maximising level, you usually get three outcomes.

Less growth. Investment falls, entrepreneurship slows, and productivity suffers as decisions are made for tax reasons rather than economic ones.

Less revenue than expected. Forecasts miss because behaviour changes. Collections disappoint even as the economy drifts.

More leakage. Avoidance rises, legal and illegal. Migration of people, profits, and intellectual property accelerates.

The fix is not a race to the bottom. It is a race to the efficient middle, a rate and a base that collect the revenue a society needs with the least distortion to work, saving, and investment.

The balancing act, tax and growth

A durable tax strategy respects four principles.

Broad base, lower rates. Fewer carve-outs and loopholes, lower marginal rates, more neutral treatment across sectors. This collects more from real activity rather than from clever structuring.

Predictability. Fewer surprise changes, clear multi-year paths. Investment hates uncertainty more than it hates fair taxes.

Simplicity and enforcement. Simple rules with credible enforcement reduce avoidance without punishing legitimate risk taking.

Competitiveness. Set rates with an eye to global mobility. High skill labour and capital move, so the revenue peak is lower than it was a generation ago.

The Laffer Curve is not a slogan, it is a caution. Western economies have leaned on higher marginal wedges to fund rising commitments in an era of slow growth and high debt. That approach carries visible costs. A better balance is possible, one that funds the state, supports social goals, and still leaves room for growth. The curve tells us that the balance exists. Good policy finds it.