The World Changes Every Fifteen Years

Understanding human cycles

Historians and political scientists have long debated whether history moves in cycles. The idea that change comes not as a smooth curve but in sharp turns has deep roots in academic literature. One recurring theme is that major shifts in economics, politics, and society seem to arrive in bursts of roughly fifteen years. It is not a fixed law, but a pattern that appears often enough to be worth attention.

The concept has echoes in the work of Arthur Schlesinger Jr, who argued in The Cycles of American History (1986) that the United States alternated between reformist and conservative eras. Though his timeline focused on thirty-year swings, his point was that societies do not progress in a straight line. Instead, periods of stability are broken by sharp pivots.

More recent scholarship has explored the rhythm of financial and political crises. David Hackett Fischer’s The Great Wave (1996) mapped centuries of inflationary cycles, while Charles Kindleberger’s Manias, Panics, and Crashes (1978) charted the recurrence of financial upheaval. These works do not speak of fifteen years precisely, but when one maps the data, many shocks do appear clustered around that interval.

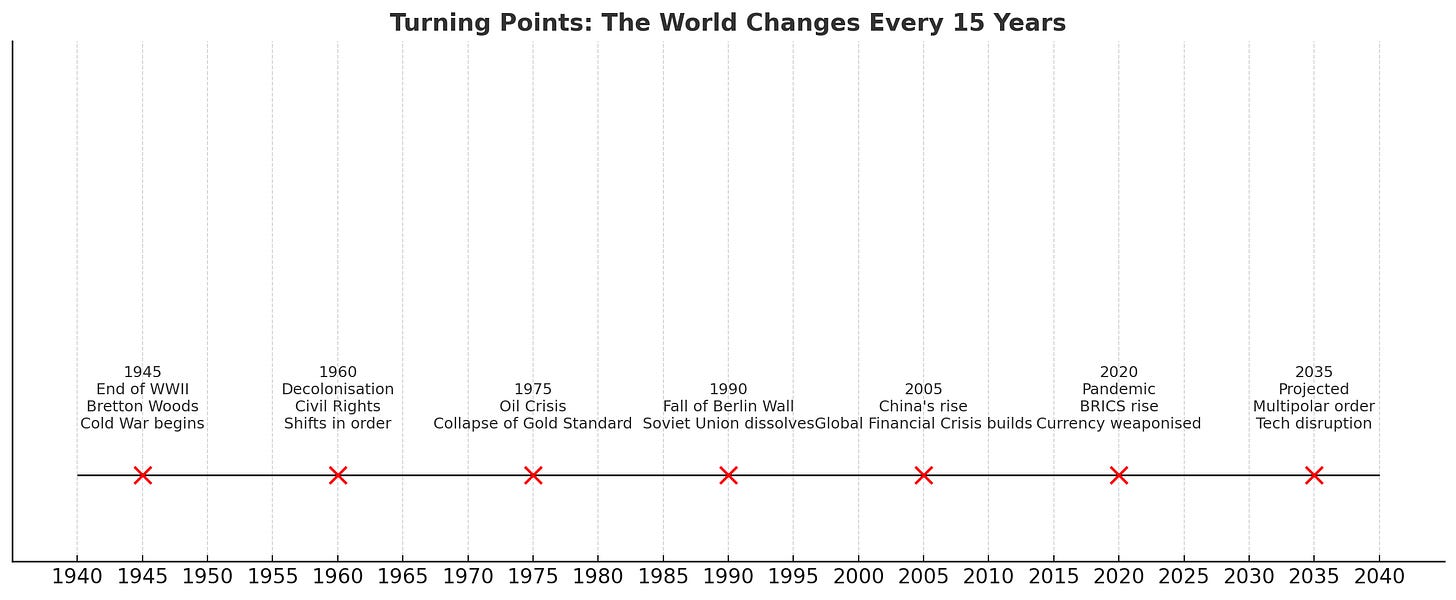

Consider some examples. The late 1940s brought the Bretton Woods system, the rebuilding of Europe, and the dawn of the Cold War. By the early 1960s, the postwar order was visibly shifting as decolonisation swept across Asia and Africa. Fifteen years later, in the mid-1970s, the oil crisis and the collapse of the gold standard transformed global economics. Another fifteen years took us to the late 1980s and early 1990s, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. By the mid-2000s, we faced the rise of China as a world power and the build-up to the financial crisis. Around 2020, another inflection point arrived with the pandemic, the weaponisation of currencies, and the rise of multipolar blocs like BRICS.

Sociologists often note that a fifteen-year period roughly matches the time it takes for a new cohort to enter adulthood. A generation of students graduates, enters the workforce, and begins to demand change. Ideas once fringe become mainstream. The old guard retires. This demographic turnover adds fuel to the cyclical fires. Political scientist Samuel Huntington touched on this dynamic in Political Order in Changing Societies (1968), arguing that rapid social mobilisation often outpaces institutions’ ability to adapt, creating periods of instability.

Technology also advances in waves that often map to this horizon. Fifteen years separates the early internet of the mid-1990s from the rise of smartphones around 2010. Another fifteen years brings us to the explosion of artificial intelligence and blockchain in the mid-2020s. Each of these innovations reshaped economics, politics, and daily life as profoundly as any war or treaty.

The key point is not that fifteen years is a mystical number, but that history seems to move in punctuated equilibrium. Stability holds for a time, then pressure builds, then a rupture. When viewed in hindsight, the breaks appear obvious, even inevitable. Living through them, they are experienced as shocks.

This pattern carries an unsettling implication. If the last great rupture was around 2020, then the world we live in today is still in the early years of a new cycle. The contours are not yet fixed, but the direction is clear. Dollar hegemony is eroding. Multipolar blocs are rising. Technology is rewriting the rules of money, trade, and even truth itself. By the mid-2030s, the world will likely look as unrecognisable to us as 1990 looked to those who had lived through 1975.

Academics often resist the determinism of cycles, warning that no theory can predict history with precision. Yet the evidence is overwhelming that shocks come in clusters. Every fifteen years, the world seems to shed its old skin. That is not prophecy, it is pattern. And for those willing to recognise it, the next rupture is not an event to be surprised by, but one to be prepared for.